Summary:

Common SCM inventory golden rules are: (a) avoid situations where inventory and demand are out of balance, those slow-moving low margin products add no value to the firm and (b) production campaigns result in unnecessary inventory. Although the SCM organization and factory are part of the same demand-supply network (DSN) they are often culturally distinct with different orientations when they work on the ongoing challenge. The purpose of this is to highlight the factory perspective on costs and complexity. We demonstrate (a) the slow-moving low-profit margin products vilified by experts in SCM have real value and (b) the cost and time associated with a changeover or sequence-dependent setup cannot adequately be represented with a single set of values, since this is risk management which requires stochastic or probabilistic decision analysis. The failure of an organization and /or its SCM partner to capture the factory perspective is an institutionalized disaster waiting to happen.

Introduction

Two common mantras in supply chain management (SCM) are (a) the importance of real costs in areas from inventory management to creating a production schedule and (b) incorporating too much complexity into a model substantially reduces, not increases, the value of the model to the firm. Loosely, complexity is defined as characteristics of the demand-supply network (DSN) that are difficult to represent in simple data structures and only relevant in the lower decision tiers. These mantra’s drive these common SCM inventory golden rules that require scolding the organization when:

- The relationship between inventory and demand is out of balance – proportionally more inventory on low demand products than high demand products.

- Those slow-moving low margin products have no value to the firm

- Large campaigns (building a lot of one product at one time), which are challenging to model, builds unnecessary inventory, and reduces the firm’s flexibility hurting the financial health of the organization simply to accommodate out-of-date factory preferences.

While SCM experts have APICs manuals on their shelves, factory folks are reading Factory Physics and studying cost accounting for factories. The reality is few SCM experts have lived in a factory setting and few factory folks have spent much time in the SCM world – but the factory is ground zero for supply chains as we are witnessing with the COVID vaccine. The purpose of this blog is to explain a basic costing challenge in factories and their impact on critical SCM analysis and decisions. Factories are defined as any organization with substantial capital and reasonably fixed labor costs and a significant time delay is needed for remission. There are wide ranges or organizations that meet this definition such as the production of semiconductor-based packaged goods (SBPG – critical to computers, cell phones, automobiles), chemicals for plastics, cosmetics, cheese, hospitals (health care systems), etc.

Factory Perspective

In the following sections we will briefly describe:

- Most costs are fixed, which makes them variable.

- Limiting risk – a challenge in a single cost for risk which is a stochastic entity.

- Unused capacity is lost forever.

- The ongoing question: with a given capacity how much can the factory produce, or given production requirements how much capacity do you need?

- And their impact on critical SCM analysis and decisions.

The failure to incorporate this perspective into a full SCM analysis is an institutionalized disaster waiting to happen.

Most Costs are Fixed, Which Makes Them Variable

In the 1980s there was a plaque on the wall of the manager of advanced industrial engineering (AIE) at the factory in Essex Junction, VT reading “Most of the costs for factory are fixed, which makes them variable”. Meaning these costs exist, whether any manufacturing occurs or not, but they need to be allocated to the products being manufactured.

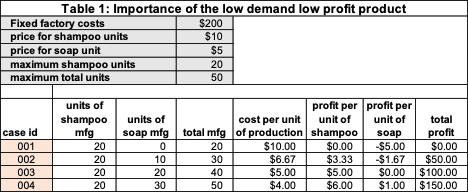

Simple example. The weekly fixed cost for the factory is $200 and the maximum number of parts the factory can make per week is 50. The fixed cost is allocated across the number of parts made. If the factory makes 50 parts, then the cost per part is $4 (=$200/50). If the factory makes 10 parts, then the cost per part is $20 (=$200/10). The cost of any part is dependent on the total number of parts produced.

Continuing our example, assume the factory makes two products:

- High-end shampoo that it can sell at $10 per unit, but the maximum demand is 20 and it has a short shelf life.

- Low-end soap that it can sell at $5, with slow demand but a very long shelf life.

If the factory only makes 20 units of the shampoo and does not make any soap, the cost for shampoo is $10 (=$200/20). Since the price is $10, the profit is ZERO. If the factory makes 20 units of shampoo and 10 units of soap, the cost per unit is $6.67 and the profit is $3.33. Table 1 demonstrates how critical soap is to financial success. Imagine that – the slow-moving low-profit margin products vilified by experts in SCM have real value – this failure is an institutionalized disaster waiting to happen.

Limiting Risk – Challenge in a Single Cost for Risk

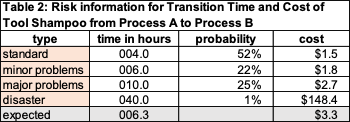

A prime concern for every factory is limiting risk from an unplanned event that idles capacity – often called a manufacturing excursion. There are three components to limit: the probability of occurrence, the time to repair the excursion (resume normal production), and the cost to the organization. A changeover or transition of the manufacturing process on a tool from process A to process B are risk points. Risk, whether for a tool or car insurance, is a stochastic event. For example, the successful transition of the tool from process A to B might take 2 hours, 4 hours, 10 hours, or 40 hours. Table 2 has an example of the components of risk. We have four classes from standard to disaster. Observe the costs increase exponentially. When the SCM expert arrives and asks for a single value for time and cost the factory person might respond, “We do not have that value.” In fact, they are thinking of this table. The model does not have risk, so the SCM expert might insist on a single value and use the expected value (last row of Table 2). We now have a cultural disconnect and an institutionalized disaster waiting to happen.

Unused Capacity is Lost Forever.

For a factory, the most precious commodity is capacity, once lost it can never be recovered, especially since 24 by 7 operations is increasingly the standard. Unused can come in different forms, a few are:

- Down for standard maintenance

- Down for changeover or transition

- Waiting- available to process material, but no material to process

Often the SCM world and factory world have different emotional reactions to unused capacity. When the optimization model indicates capacity should be idle, the factory is suspicious and is looking for an explanation why. There is an entire factory underground that puts a warning on optimization. For example, a question that often comes up – “I heard there can be more than one optimal solution?”

Ongoing Factory Question

The ongoing question for every factory director is: “Given capacity, how much can the factory produce?” More precisely which demand or need can be met and when. Alternatively, or given production requirements, how much capacity do you need to achieve this. Either way, it is the factory director that must make and meet the commitment – not the SCM folks. A successful director is aware of the complexities (campaigns, sequence-dependent setups, batch size, alternative manufacturing processes, the time between failures, etc.) and suspicious of the statement: we do not need to handle this complexity. It is incumbent on the modeler to demonstrate this statement is true. Second, the application of value to them is one that can bring smarts to their dispatch/scheduling. The director’s rule of thumb is “complexity exists whether you ignore it or not, best not to ignore it.”

Conclusion:

Although the SCM organization and factory are part of the same demand-supply network (DSN) they are often culturally distinct with different orientations when they work on the ongoing challenge of improving the organization’s performance through more intelligent decisions. The purpose of this blog is to highlight the factory perspective on costs and complexity. We demonstrated the slow-moving low-profit margin products vilified by experts in SCM have real value – this failure is an institutionalized disaster waiting to happen. The cost and time associated with a changeover or sequence-dependent setup can not adequately be represented with a single set of values, since this is risk management that requires stochastic or probabilistic decision analysis. The ability to handle manufacturing complexities such as campaigns or batch size is critical to the factory’s ability to meet committed near-term production objectives. The reality is the optimization time window is shrinking, which drives the need for community intelligence.