In our 3 previous articles, Balancing Cash Cost and Service: The Supply Chain Triangle, Best Practice Frontier in the 3D Supply Chain Triangle and Financial Benchmarking for Inventory Turns and Working Capital we have shown there is a lack of alignment for targets on the cash, the cost and the service side of what we have defined as the Supply Chain Triangle. We have looked at the EBIT per inventory $ or per working capital $ to define a best-practice frontier. That frontier can then be used for setting balanced targets on EBIT% versus Inventory Turns or EBIT% versus CCC.

The resulting balanced targets typically pointed in 2 possible directions:

- Either a combined improvement on EBIT% and Inventory Turns (or CCC)

- or a more focused improvement on EBIT% for the current Inventory Turns (or CCC)

As we will now argue, the choice between these 2 is the choice of strategy. To do so, we will map the 3 strategic options proposed by Treacy & Wiersema to the Supply Chain Triangle.

The 3 strategic options proposed by Treacy & Wiersema

Treacy & Wiersema (Treacy, M., Wiersema, F., The Discipline of Market Leaders, Basic Books, 1995) argues that in any sector, a company can be a market leader by excelling in 1 of 3 dimensions only. Either the company is a product leader, is a leader by operational excellence, or is a leader in customer intimacy. We will give our interpretation of these three extremes and then analyze the impact on the supply chain triangle.

1. Product Leader

A Product Leader prevails by having the best product, again and again. They are focused on generating a stream of innovative products or services that sell at a significant premium. The investments in product development and marketing are significant. In fact, with each new product, the product leader is betting their business. A success story will give an above normal return. Two failures in a row can destroy the company. Apple would probably serve as an example. For years it stood out with a stream of new products ranging from the i-pod, the i-phone and the i-pad to i-tunes and the i-cloud. But nothing lasts forever. Fierce competition from Google and Samsung is turning the heat up on Apple.

2. Operational Excellence Leader

An Opex (Operational Excellence) leader prevails by low-cost and hassle-free, no-nonsense, easy service. They are focused on being the cheapest in combination with easy-to-deal-with. Commonly used examples are the low-cost airlines like Southwest or Ryanair who have disrupted the airline sector by a relentless focus on low cost and hassle-free service.

3. Customer Intimacy Leader

Some companies are not the cheapest, nor the first on the market. They prevail by having an intimate knowledge of their customer. The key asset in customer intimacy is the knowledge of the customer and the relation with that customer. Serving the full range of a customers’ needs will exceed the core competences of the intimacy leader. It is key for the Intimacy leader to expand their capabilities by forging key partnerships. The integrated approach of the Intimacy leader is valued at a premium compared to an Opex leader. The premium is driven by the ‘comfort’ to the customer of the ‘one-stop-shop’. It’s a premium because of convenience.

Mapping Treacy & Wiersema to the Supply Chain Triangle

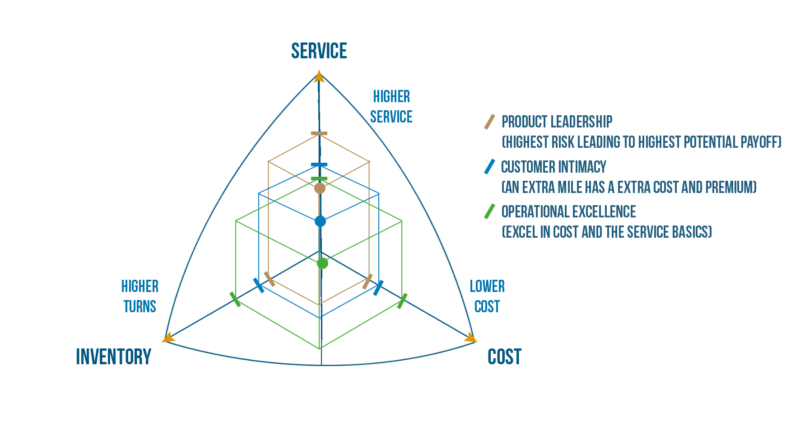

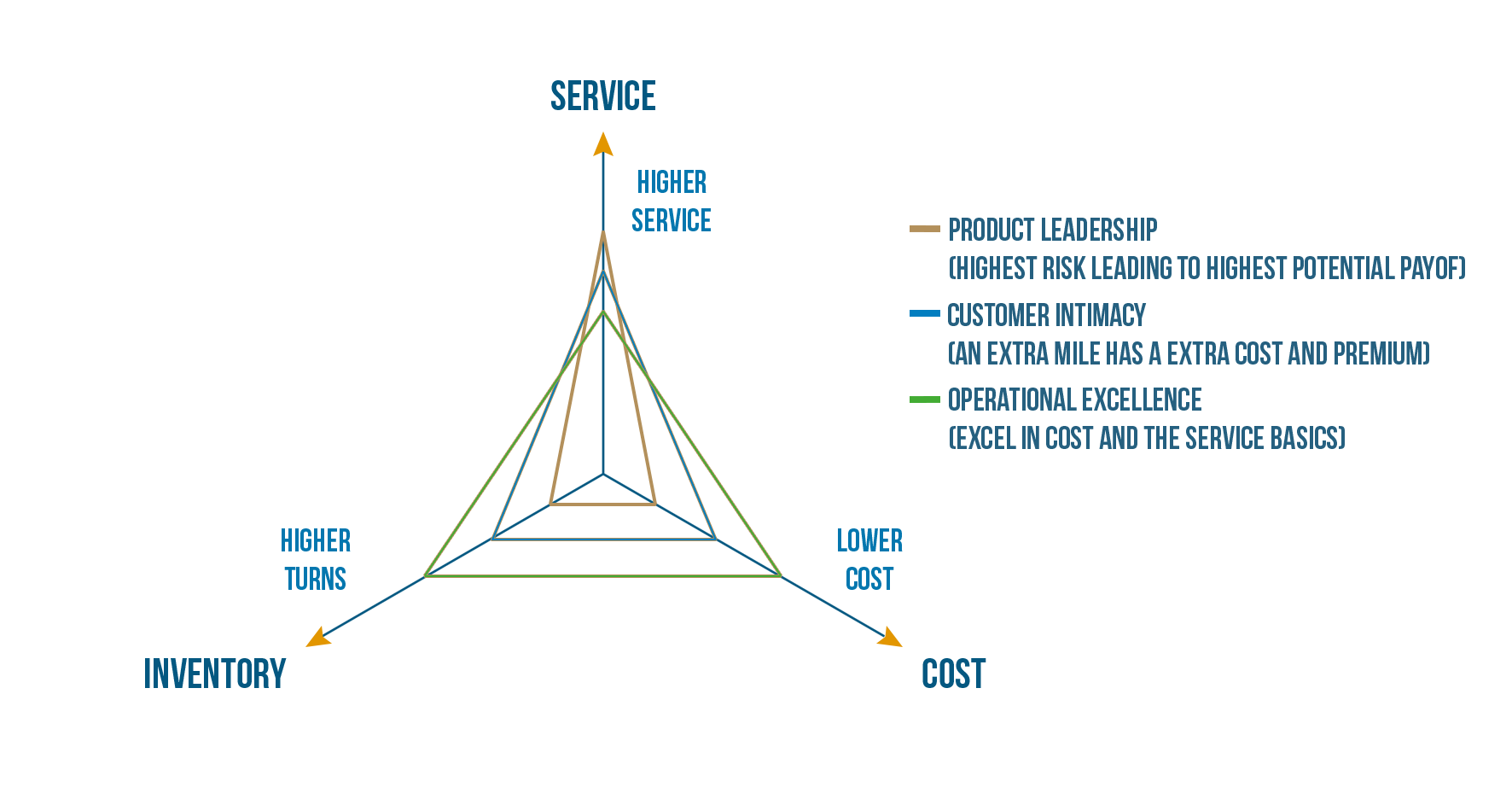

In Figure 1 we’ve started by mapping the 3 strategic options of Treacy & Wiersema to inventory axis of the Supply Chain Triangle.

The reason for an Opex leader to work with minimal inventory (or the highest turns) is the inventory cost. Less SKU’s means easier operations, lower cost per unit, less risk and write-offs. Opex leaders typically have the smallest product portfolios, are ruthless on the value-add of an extra SKU. Simplicity drives the efficiency on which the Opex leader prevails.

A Product leader has the highest inventory risk. Imagine the situation of Apple when launching the i-pod, the i-phone or the i-pad. How to forecast sales of a new product in a new market? The uncertainty is very high. If the forecast is too high and the product is a failure, you can be left with a lot of unsold inventory. Given the fast pace of technological innovations, unsold inventory is at a high risk of becoming obsolete. If the forecast is too low, and the product is a hit, it can take weeks or months for the supply chain to catch up. Delivery problems will affect sales and give time to the competition to respond. Moreover innovative products typically sell at a high margin. All this favors having ‘too much’ stock over ‘not having enough’. In a series of innovative products, you know that some will fail. These will create unsold inventories. This is the risk on which the product leader thrives.

To be on the edge, product leaders have to work with innovative components and suppliers. New components have a higher risk for quality issues, frequent revisions, … which adds to the overall inventory the product leader is carrying.

For the Intimacy leader, being the 1-stop-shop for your customer typically comes with complexity. An intimacy leader has a broad range of products and services. Not all of these products may individually lead to a profit. The profit is judged on the level of the client, not on the level of the SKU.

We have plotted the Intimacy leader in between the Opex leader and the Product leader for inventory turns. Their higher complexity will lead to lower turns than the Opex leader. Their premium will be lower than that of the Product leader, pushing him to keep control.

Notice that none of the strategies is focused on ‘cash’. They all have to trade-off whether an extra inventory cost is set off by higher margins. Carrying more inventory is allowed. As long as the margin generated per inventory $ goes up, we assume financial markets will provide you with the necessary cash. Also remember that in any industry you’ll find leading companies in each of the dimensions.

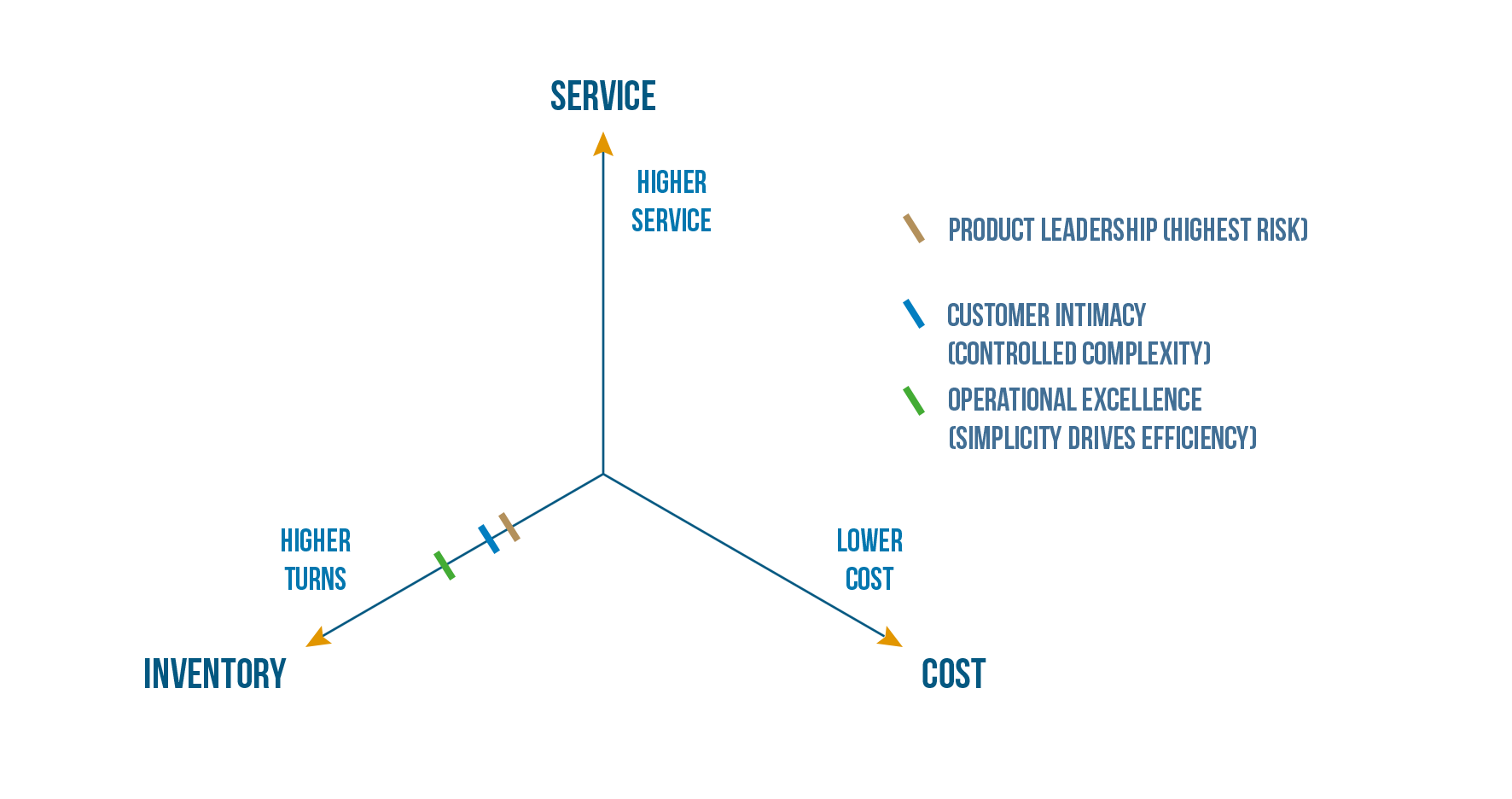

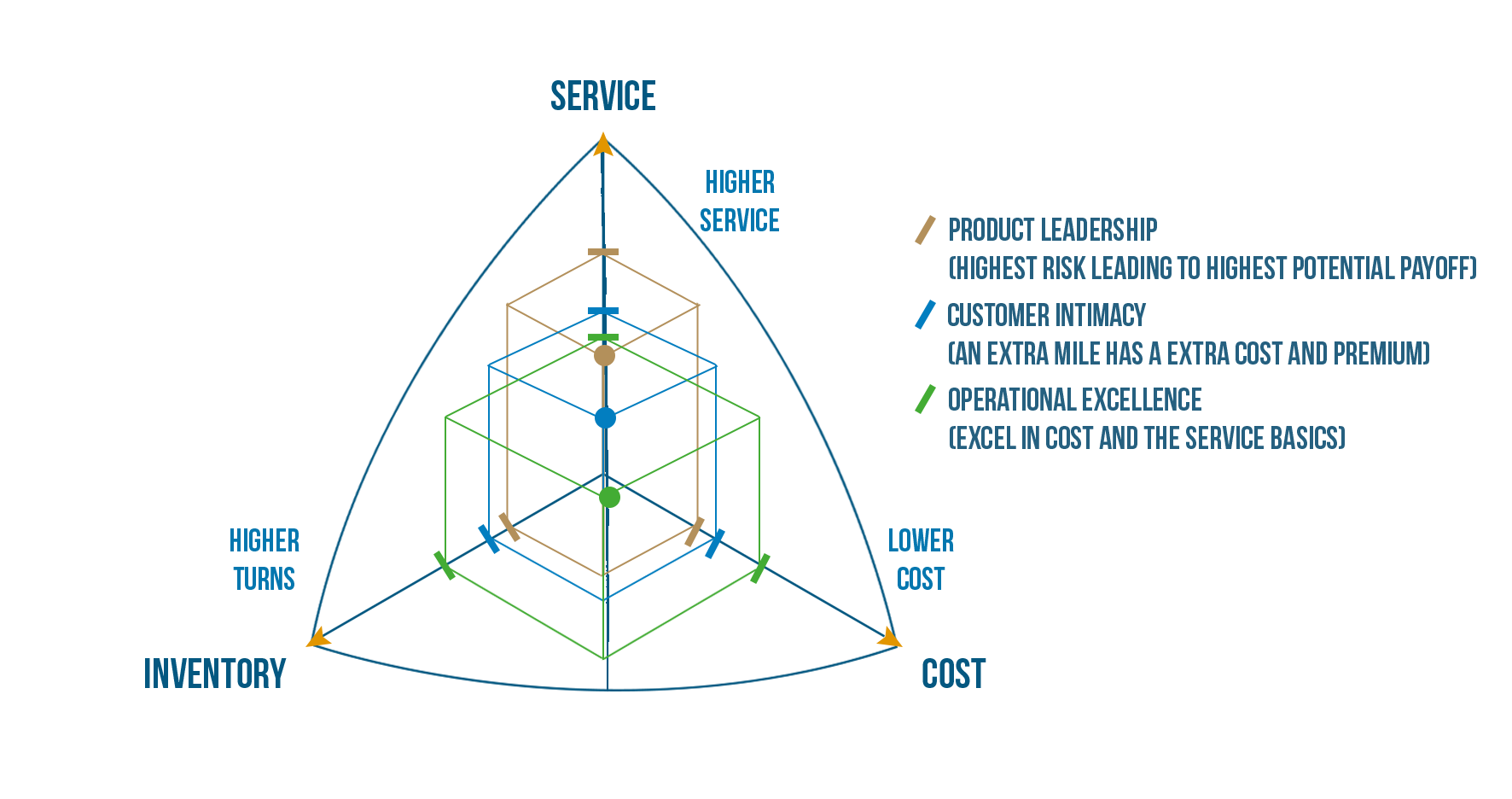

Figure 2 maps the 3 strategic options to the service dimension of the Supply Chain triangle.

In our perception, a true product leader goes beyond service by creating emotional value. Customers pay a double premium because of that emotion, to feel special, to be part of the clan that ‘owns something special’. That’s why customers queue up at night in front of the store the day of a product release.

Product leaders extend that emotion into the buying and after sales process. Apple stores breathe the Apple spirit. They are not low cost shops. They are fashionable, playing on the emotion. In general, we expect product leaders to be highly service oriented. We ranked them highest.

We have ranked the ‘customer intimacy’ player above the ‘operational excellence’ player. It’s not that Opex doesn’t care about service. Remember that ‘hassle-free service’ is one of the key aspects of the Opex discipline. The level of service however is lower because of the cost focus. In customer intimacy we are willing to go the extra mile for the customer, we extend the service and expect a premium in return.

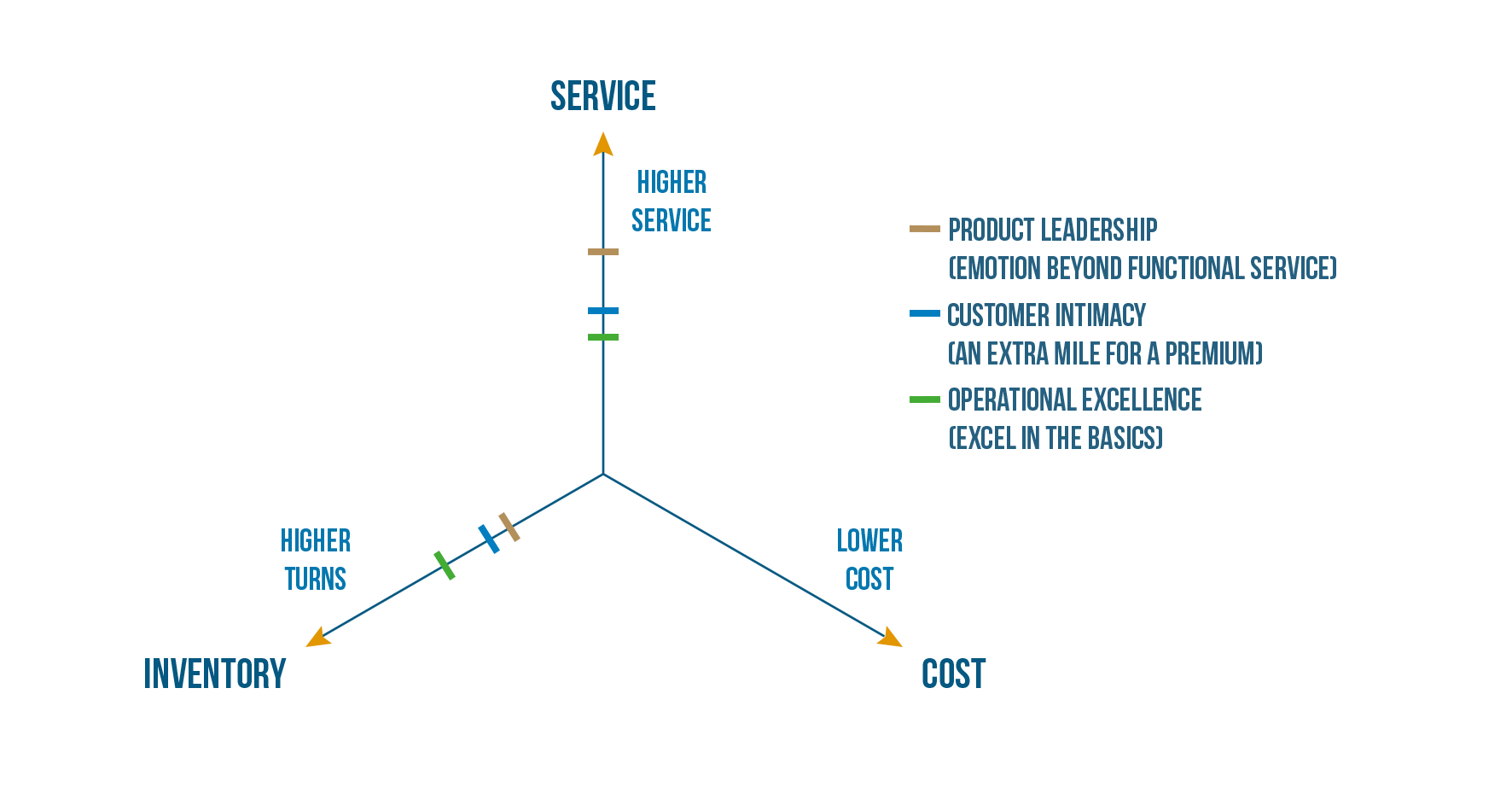

Finally, in Figure 3 we have also mapped the 3 strategic options to the cost side of the Supply Chain Triangle.

The Opex leader should be the cost leader. Every fiber in their organization is focused on lowest cost. Their cost position is the reference on the cost axis. The extra mile of the ‘customer intimacy player’ comes at an extra cost. That’s why we ranked them higher.

Finally, the Product Leader has the highest cost. Being the first on the market, again and again, requires significant investments in R&D. You may have the best product, but if nobody knows it, it will not sell. As a result, product leaders also invest a significant amount of money in marketing and sales. Playing the emotion, is part of the product leaders game. Next to R&D and marketing, a product leader will also have the highest supply chain cost. Forecasting the sales of a new product in a new market (e.g. the first i-pad) comes with a high error. The corresponding supply chain will focus on flexibility, not efficiency. The flexibility will come from multi-sourcing, ample capacity, fast transportation modes, … this flexibility will come at a cost. However, if the product is a success, the premium paid by the customer will lead to premium profitability for the product leader. It’s the highest risk game. The highest risk typically leads to the highest potential payoff.

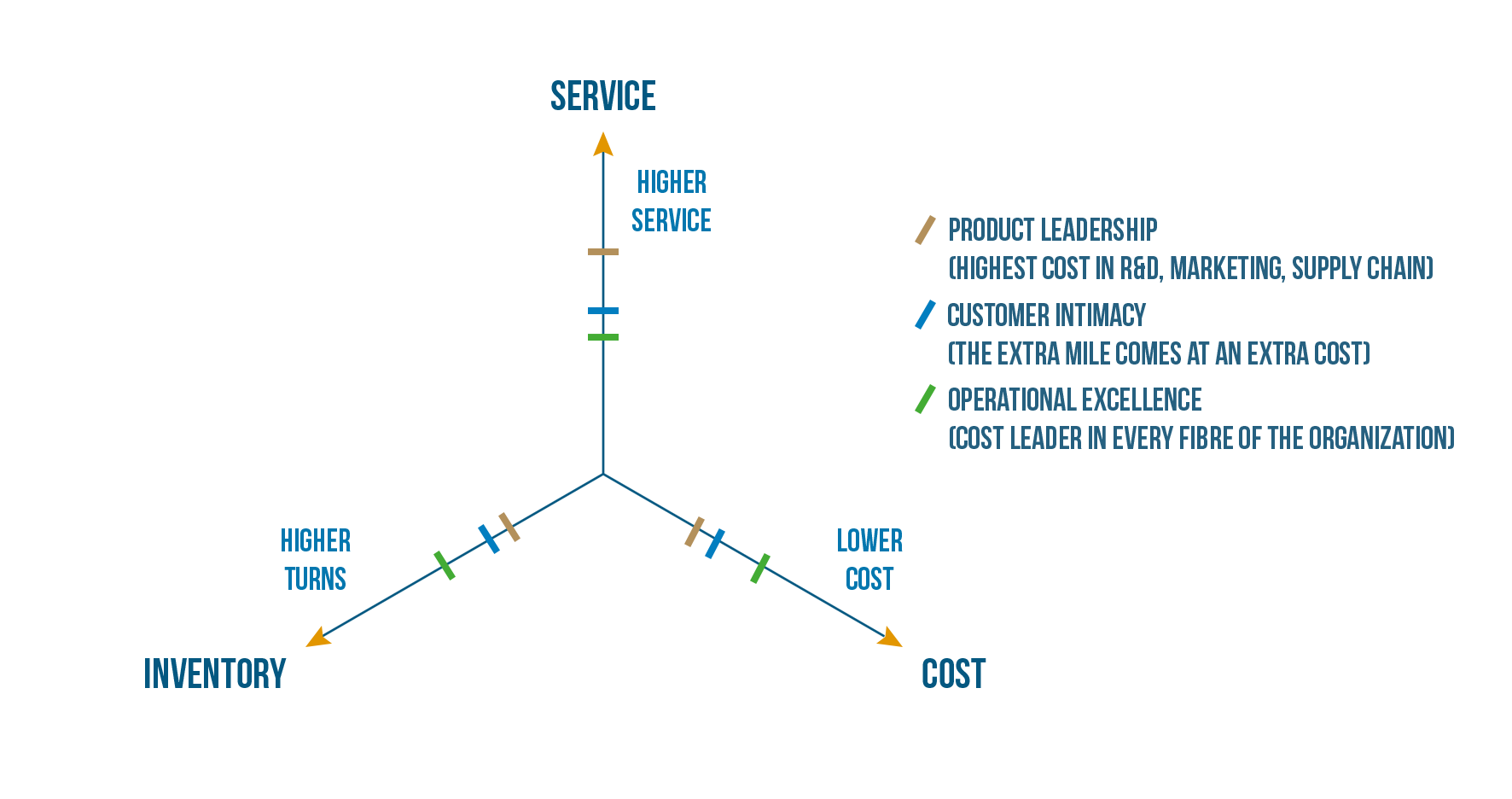

Figure 4 shows the resulting profiles for the product leader, the customer intimacy leader and the opex leader. 3 different profiles, each of which can earn market leadership according to Treacy & Wiersema, as long as executed in a disciplined way, hence the appropriate title of their book “The discipline of market leaders”.

Figure 5 is showing the same, but again maps it in 3D, as we did in our blog “Benchmarking and the Best Practice Frontier in the Supply Chain Triangle”. Remember that the ‘surface’ was the ‘best-practice surface’. Companies on the surface typically need to give in on 1 of the dimensions if they want to improve on another. Companies below the surface can improve on the 3 dimension at the same time.

The mapping in Figure 5 sheds some extra light on the 3 options proposed by Treacy and Wiersema. They are 3 strategic options on the ‘best practice surface’.

The ‘product leadership’ and the ‘cost leadership’ are probably the most easy to understand, as they choose to excel in 1 dimension of the supply chain triangle.

Notice that we assume that cost and inventory go together. Next to cash consumed, inventory always translates into the cost dimension. Inventory carries a cost for the room, the rent and the risk. Inventory also hides inefficiencies. That’s another reason for an Opex leader to work with minimal inventories.

Customer intimacy is probably the most difficult one. We add extra miles, which come at an extra cost. We need to ensure they also come at an extra premium.

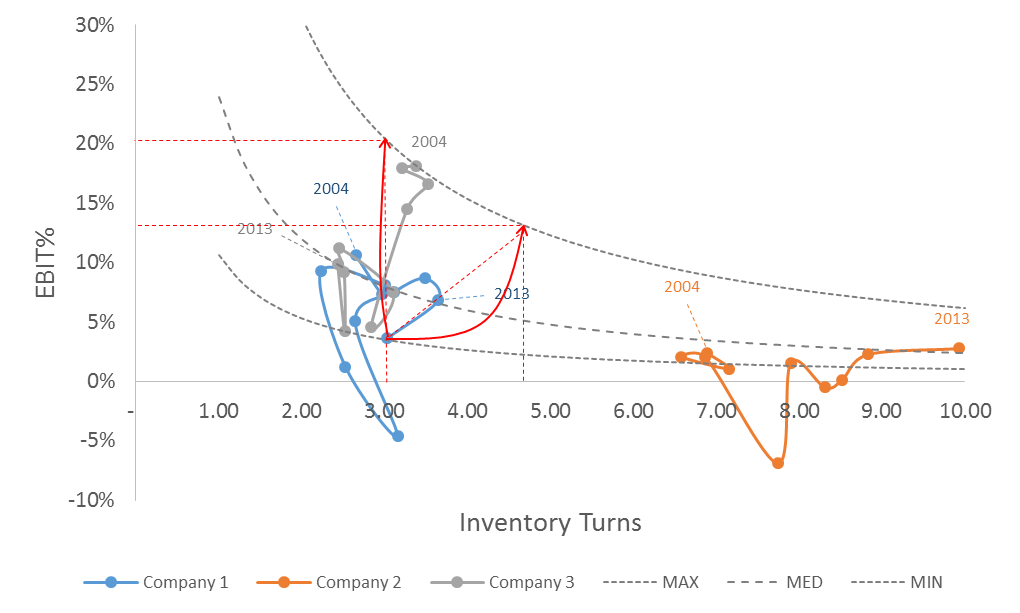

A strategic trade-off between EBIT and Inventory Turns

In our previous blogs “Benchmarking and the Best Practice Frontier in the Supply Chain Triangle” and “Financial Benchmarking for Inventory Turns and Working Capital”, we were still left with a choice between two more aggressive targets for our benchmark Company 1, cfr. Figure 6, either

- Extend the turns from 3.75 to around 4.75 for an EBIT% of around 13%

- Either boost EBIT% to 20% if inventory turns stay around 3

The choice between the two is a strategic choice. As we’ve shown in Figure 5, it is the choice between a ‘product leadership’ and a ‘customer intimacy’ position.

A product leader will experience superior profitability but with lower turns. Company 1 historically has been a product leader. Staying true to the roots would plead for keeping the current level of complexity and maximum focus on new high margin products.

The alternative is to go for a customer intimacy position. In this case we don’t go for the newest and the highest spec, but go for a full coverage to a selected number of market segments, part of it with our own products and developments, part of it with products we source from partners or 3d party manufacturing. Company 1 has been moving down this path since 2010. If it chooses to continue this path, it should probably take it more to the extreme. Cut some of the apparently less performing, more complex business to boost inventory turns. Boost EBIT% by reducing R&D spending in line with the new ‘customer intimacy’ position. Boost EBIT% by squeezing more margin out of the existing customer relations.

Where the Orbit charts and analyzing the EBIT per inventory $ have helped to define the options. We need a strategic framework to make the right decisions!

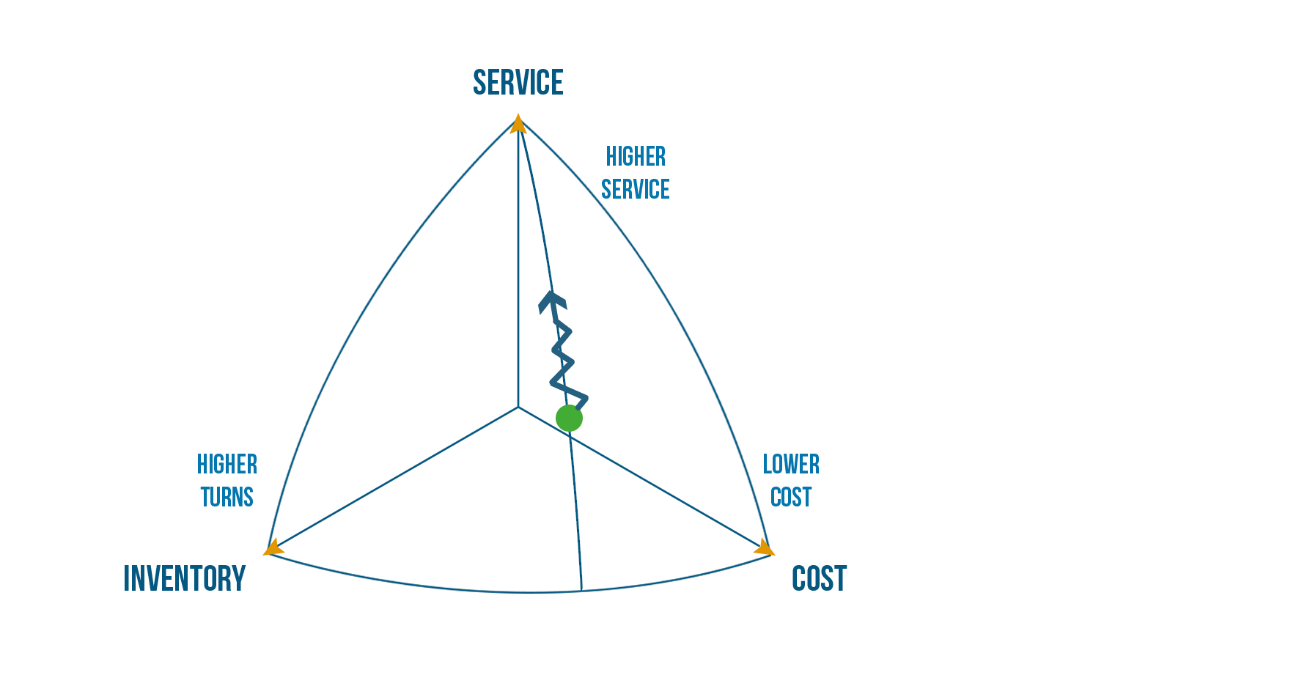

Complexity creep. The cost of complexity. Good and bad complexity.

We can also use the 3D supply chain triangle to talk about complexity. Figure 7 shows the so called complexity creep. I notice that in companies, over time, complexity increases. We start adding products, we allow customer specific requirements in transports, in product development, … It is the natural push of sales, marketing, product management, R&D, … to add ‘new stuff’ to the business. If the business is under pressure, this will be accelerated. It is the ‘pulling on the service angle’ we introduced in our first blog ‘Balancing Cash Cost and Service. The Supply Chain Triangle.’

A lot of this added complexity goes ‘unnoticed’ without passing any ‘formal approval’ or ‘decision making’ process. If it does, it will still typically go unnoticed as it is a ‘piecemeal’ evolution. It’s not a big bang, it’s a creep.

For a company working on the best practice frontier, the added complexity comes at an extra cost and with extra inventory. There is no way around. If the extra complexity is not set off by an extra margin, it is classified as bad complexity, and it should be banished. If there is an extra margin, it could be classified as ‘good’ complexity. There is a big caveat however …

Don’t treat complexity in an incremental or an opportunistic way. There will be cases where a sales person has a good story on how this extra complexity for this customer will pay off by this or that extra margin. Treat complexity from a strategic perspective. Define the level of complexity you want to carry top-down, not bottom-up.

If you’re an Opex player, you don’t want the extra complexity. Take the recommendation from Treacy & Wiersema. You will only succeed by making a choice and by disciplined execution. It may be tempting to add some more products, if it supports profitability, especially if your business is under pressure. It is the wrong strategic choice. If as an Opex leader you’re under pressure … try harder! Stay true to yourself. Find extra ways to lower costs. As Treacy and Wiersema convincingly explain, you can only be the best in 1 discipline. Avoid getting stuck in the middle. Once you’ve made a choice, it needs to be embedded in every fibre of your organization. Once it’s embedded, you can never revert. It becomes your DNA.

If you’re under pressure as a Customer Intimacy or a Product leader, it may be tempting to cut costs, try to rationalize product portfolios, customer service, … Don’t go blindly. Define the level of complexity you need to thrive as a Customer Intimacy or a Product leader. Try harder in the chosen discipline. If you have built your organization to be product leader, don’t try to turn it into a cost leader. You are likely to fail as every fiber in your organization is focused on innovation, not cost. Ask yourself why you failed as a product leader in the first place. Don’t change the subject. What will it take to rebound as a product leader? Convince shareholders why they should stay true and make that extra investment. It’s not the easy way, but according the Treacy & Wiersema, it’s the only way.

So when looking at the Supply Chain Triangle we should remember that targets on EBIT and Inventory should be aligned with each other and they should be aligned with your strategic positioning!

In conclusion, we should remember that making the choice on where to go with the EBIT versus Inventory strongly depends on your strategy. From Treacy & Wiersema we learn that being successful, requires explicit choices. You need to take it all the way. Once you’ve made those choices, they’re hard to revert later, as every fiber in your organization has to be realigned to your renewed positioning. We like to push hard on inventories, but we should not do it lightly. Make sure it’s aligned with your EBIT. Make sure it’s aligned with your strategy.