It was Sir Isaac Newton who told us that things not in motion will continue to be that way until acted upon by an external force. Vice versa, things that were already in motion will continue to move that particular way without a change in direction or speed unless acted upon by an external force. Today we know this as the law of inertia.

When it comes to sales and operations planning (S&OP or more generally, supply chain planning), this law applies in a big way. Companies usually settle into a rhythm over time to do things a particular way. Very likely, the particular way was started by someone who took the initiative to define the process. In other words, this individual or group was being the external force to get things rolling. Overtime however, these ways get entrenched in an organization and it becomes an impossible task to try and change them. The essential force of inertia kicks in, and because we are dealing with a whole group of people as compared to a single object in Newton’s example, the inertia is very strong. Therefore, changing out of this without an external force is near impossible. As one of our client project sponsors puts it: There are two things I hate: change, and the way things are.

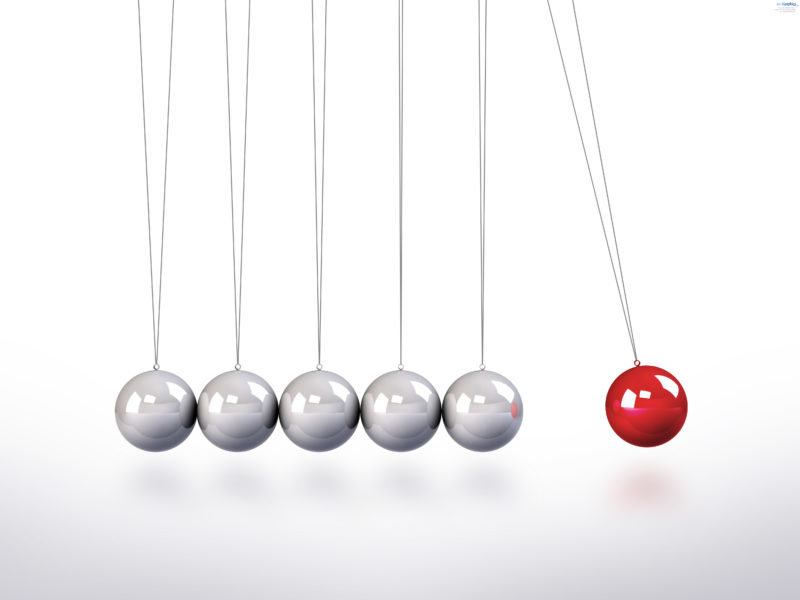

The types of external forces that can get the ball rolling include a bad business situation such as force majeure, a recession, missed customer orders, a merger with another company, the arrival of an executive from a different company, etc. Without these forces, inertia will rule supreme and at best one can see evolutionary changes. In the presence of the external forces, one might see some amount of revolutionary changes.

Once the change is implemented, the battle is surely won, but the war can still be lost. Here is when the law of entropy kicks in. A very simple explanation of this law is that all things left to their own devices will gradually decline into disorder. What this means is that unless someone is really driving the new process to newer heights, things will gradually go back to the old way of doing things. This need for continuous supply of energy to keep things running at the newer-better level is often underestimated. Therefore, over time, all S&OP processes tend to take this path.

In business terms, I recently became aware of this idea of Efficiency Drift, which sounds to me like entropy in a business system. In the blog post, the author suggests that a drift of 1.5 sigma is possible over time. Here is the direct quote: “… here is the sting in the tail – by doing nothing, things will deteriorate and waste will increase. Businesses evolve with new products, new people, and new processes but is your ERP system (and your knowledge of it) evolving with those changes?” The author’s example is on ERP systems; I suspect that the drift is only worse in S&OP processes as they are less transactional and more long term oriented.

So, there it is. Another take on why S&OP is tough and why it can be so difficult to implement and sustain. With tongue firmly in cheek, I proclaim that two scientific laws are firmly against its success. So, if you are having trouble implementing it, it is very understandable. My suggestion would be to understand these laws in action in your particular case and apply appropriate action to remedy the situation.

Like this blog? Follow us on LinkedIn or Twitter and we will send you notifications on all future blogs.